READ: "Strategic Approaches to Maritime Chokepoints in a Globalized World - Case studies in Bab el-Mandeb" by Thomas Spence (Student research paper)

BY: THOMAS SPENCE

AMERICAN UNIVERSITY OF BEIRUT

Abstract

In this paper, I investigate the ways that states approach maritime chokepoints in the context of globalization by analysing two case studies from 2018: the nationalisation of Doraleh Container Terminal and the Emirati occupation of Socotra. I begin by situating the discussion with a survey of the relevant literature on globalization and maritime history. I then identify three different methods leveraged in the case studies for establishing control (commercial, military, and diplomatic) and discuss how they relate to concepts of territorialization and deterritorialization. I continue by examining the cases at a local scale, discussing how local factors influence and are in turn influenced by the strategies used. Finally, I suggest sources of data that could be utilised to deepen our understanding of the topic and discuss directions for further study.

1. Introduction

Globalization and the ocean

Over the last thirty years, globalization has become a dominant characteristic of the world’s economic and cultural systems. Rarely is this process more evident than in the maritime sphere: global trade, for example, has grown at an extraordinary rate - more than 500% in the last 30 years (WTO, 2019). Frank Broeze even goes so far as to assert that the sea is not only a site of globalization but also a pillar of it:

“...although globalisation has become a household word, there is little recognition that our world could not function without the complex system of maritime transport sustaining intercontinental and regional trade.” (Broeze, 2017)

This sentiment hints at an aspect of globalization that Thomas Hylland Eriksen introduces in Overheating. A key feature of what Eriksen describes as runaway processes is the emergence of unintended side-effects (Eriksen, 2016) - in this case the runaway process of global trade has resulted in a loss of flexibility and the complete reliance of most countries on maritime imports for critical goods such as energy or food. Eriksen also emphasises the importance of small-scale processes on larger systems and vice versa:

“Sometimes, it is necessary to slide up in scale to see the global consequences of your actions; at other times, it is necessary to slide down in order to understand the local implications of large scale processes.” (Eriksen, 2016, p.51)

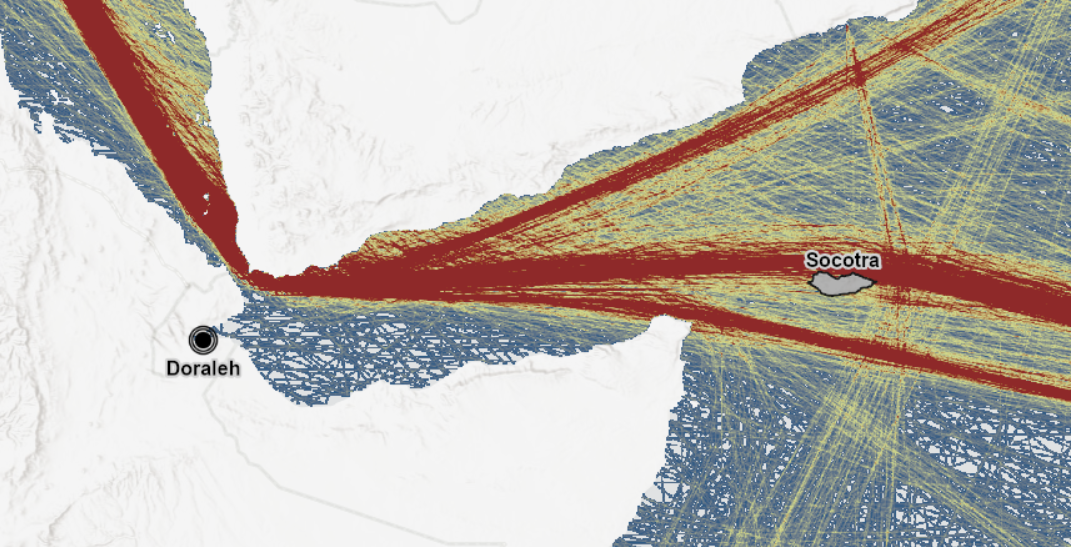

Similarly, in Friction, Anna Tsing writes about the importance of studying abstract global concepts (‘universals’) as they operate in the world, at local scales, and emphasises that “Global connections are made in fragments - although some fragments are more powerful than others.” (Tsing, 2005) These observations are true of the global trade network. The many shipping lanes on which countries are reliant converge and narrow at sites around the world where they are constrained by geography. These bottlenecks (examples of which are presented in Figure 2) form highly vulnerable nodes in the system of maritime trade - disruption of these nodes has the potential to impact systems on a global scale as shipping becomes either impossible or prohibitively time-consuming for modern requirements. They are fragments of global connections which hold a great deal of power.

Traditionally, these strategically important locations have been viewed through a geopolitical lens; an approach “concerned with the inter-relationship between territory, location, resources and power” (Dodds, 2009). With regards to marine bottlenecks, it was first formalised by Admiral Alfred Thayer Mahan in Naval Strategy (Mahan, [1911] 1991). However, even before Mahan wrote his treatise on sea power, the lens through which shipping lanes and chokepoints have been approached since the beginning of the 16th Century has been primarily geopolitical.

The early modern Portuguese seafarers Alfonso de Alberquerque and Francisco de Almeida, operating under King Manuel I, are often credited with being the first to recognise the strategic importance of controlling key nodes in global maritime networks (Ballard, 1928; Diffie & Winius, 1977). The directions issued to Almeida by Manuel I in 1505 indicate the centrality of controlling trade flows, rather than territory, to this imperial strategy:

“...nothing would serve us better than to have a fortress at the mouth of the Red Sea or near to it ... because from there we could see to it that no spices might pass to the land of the sultan of Egypt, and all those in India would lose the false notion that they could trade any more, save through us...” (Diffie & Winius, 1977)

Under this guidance, Portugal built trading posts (feitoria) and seized and fortified harbours along key shipping chokepoints around the Indian Ocean, including Hormuz, Mozambique, Colombo, and Malacca (and attempted to do the same at Aden); through these they established a near-monopoly over direct trade between Europe and Asia for almost a century.

After the Portuguese, the British and the Dutch Empires became the leading proponents of this geopolitical approach to sea lanes. The British came to adopt this stance in the 17th Century under the strategic concept of ‘Command of the Sea’, a stance neatly summarised by Gerald S. Graham:

“...protection of colonial trade need not include the defence of burdensome territorial pickings across the ocean. A growing network of overseas bases could provide essential local protection” (Graham, 1965, pp.15-16)

This concept continued to drive British imperial policy for nearly two hundred years, through the colonial acquisition of Aden, Singapore, Gibraltar, the Trucial States, and Cape Colony (the last of which was viewed even in the early 19th Century as a costly and burdensome necessity rather than a desirable possession (Graham, 1965, pp.40-41)). By 1879 the geopolitics of the sea had shifted with the development of coal-fuelled vessels, yet the British maintained this approach through the Carnarvon Commission, which considered both local and global factors to determine where coaling stations should be established to control and protect maritime trade (Gray, 2018).

Even in today’s discourse, Mahan’s geopolitical methods still hold great sway over thinkers in the field of security studies. The contemporary naval strategies of the United States (Wirtz, 2002) and China (Holmes & Yoshihara, 2008) are both influenced by Mahan.

However, this way of thinking about maritime chokepoints is inherently territorializing in that it seeks to define geographic zones of control. Adapting Deleuze and Guattarri’s concepts of absolute and relative deterritorialization (Deleuze & Guattari, 1977, 1988) provides an alternative way of thinking about these sites in the context of the modern, globalized world. These concepts are traditionally applied to cultural issues, in which absolute deterritorialization is the separation of a concept from a location. This deterritorialization is described as ‘relative’ when it is accompanied by subsequent reterritorialization. In Globalization in Question, David Harvey provides such an adaptation when he identifies one feature of globalization as a process of deterritorialization (expressed through the loss of powers by the state) and reterritorialization in the form of decentralization and global institutions; this results in it being “harder for any core power to exercise discipline over others and easier for peripheral powers to insert themselves into the capitalist competitive game” (Harvey, 1995).

The deterritorialization of the sea is most evident in aspects of the modern law of the sea. The foundations for these laws, as set forth in the UNCLOS III treaty, were laid by Hugo Grotius in Mare Liberum in 1609. While Grotius was an early proponent of freedom of navigation on religious grounds (Grotius & Armitage, 2004), his work was frequently used in service of mercantilist naval policies due to his arguments regarding just wars. By the middle of the 20th Century, the question of sovereignty over the sea had come to the fore as resource extraction became more feasible. Increasing territorial claims (such as the Truman Declaration) and conflict over oceanic resources (e.g. the Lobster War) eventually led to the adoption of the UNCLOS treaties to set out the Law of the Sea (Moran, 2002). Among other things, this enshrined Grotius’ principle of Freedom of Navigation in law for international straits. This example of relative deterritorialization, removing straits from their geographic context by law and placing them under global institutions, thereby levelling the playing field for all actors is emblematic of the approach of globalization to such chokepoints.

Reconciling these approaches

It is clear that there is a tension between these two approaches to maritime chokepoints - as Brian Blouet summarises, “Globalization is the opening of national space to the free flow of goods, capital, and ideas.” whereas “Geopolitical policies seek to establish national or imperial control over space” (Blouet, 2004). As such, we must ask: How do states interact with maritime chokepoints in the 21st century? Are their actions based on geopolitical, territorializing approaches, or are they rooted in the globalized world of deterritorialization and freedom of navigation?

This paper aims to investigate these questions through the analysis of two contemporary case studies, both of which took place in 2018 around Bab el-Mandeb (Figure 1): the commercial dispute that erupted between DP World and the government of Djibouti over Doraleh Container Terminal, and the military occupation of the Yemeni island of Socotra by the United Arab Emirates.

2. Bab el-Mandeb

Bab el-Mandeb is a strait connecting the Red Sea with the Gulf of Aden. It is situated between Djibouti and Yemen, and at its narrowest is only 18 miles wide. More than 50 million tons of agricultural products (Chatham House, 2017) and 1,750 million barrels of oil (EIA, 2017) pass through this waterway each year, making it a critical chokepoint for international trade - a status it has held since the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 (Koburger, 1992). Due to ongoing instability in the region, it is ranked as one of the highest-risk bottlenecks for international trade (Kosai & Unesaki, 2016).

Case study 1: Doraleh Container Terminal

Doraleh Container Terminal (DCT) is a facility at the port of Djibouti with an annual capacity of 1.25 million TEUs (20-foot equivalent units, a standard shipping container). It is the only modern deepwater port that serves Bab el-Mandeb and the Horn of Africa. The terminal was built from 2006 to 2008 by DP World, an Emirati port services company. After construction was completed, DP World managed the operations of the port and owned a 33.34% stake in it, with the Djiboutian government holding the remaining 66.66% (Wilson, 2018).

While the two joint venture partners had rarely been more than cordial, relations between Djibouti and DP World began to deteriorate as a litany of complaints built up. In 2012, Djibouti accused DP World of a number of wrongdoings including bribery, profiteering, and deliberately suppressing Doraleh’s development; several arbitration cases were then launched in international courts (Dahir, 2019). The following year, another party entered the picture as Djibouti sold 23.5% of its stake to a state-owned Chinese rm, China Merchant Port Holdings (CMPH); DP World responded by claiming that this was a breach of contract by the Djiboutian government. Mistrust between Djibouti and the UAE deepened in 2015 when Djibouti rebuffed attempts by the UAE & Saudi Arabia to utilise DP World’s infrastructure as a military launch-point for the Yemeni conflict (International Crisis Group, 2018). Compounding these relationship issues was the growing Chinese involvement in Djibouti’s ports, notably through the construction of an alternative facility, Doraleh Multipurpose Port, in 2017.

Conflicts between the partners in DCT reached their apex in 2018 when the Djiboutian government unilaterally ended their contract with DP World and then nationalised the terminal. A series of legal challenges were opened by DP World against the Djiboutian government and CMPH in courts in London and Hong Kong. Since the nationalisation, operations have been handed over to CMPH, who are further increasing their control of the port (Paris, 2019).

Case study 2: Socotra

The Yemeni island of Socotra lies off the Horn of Africa and holds a commanding position at the entrance to the Gulf of Aden and Bab el-Mandeb. Its capital, Hadibu, is home to the island’s only port and airport (which has a 3,000m runway suitable for military use). Socotra was heavily damaged by two cyclones, Chapala and Megh, in a single week in 2015. Following this, the UAE provided $1.64bn of aid to Yemen, including the development of the Zayed Residential City complex on Socotra (Al-Karimi, 2017). Development continued on the island (including the renovation of Hawlaf Port) leading to disputes over conservation of the island’s natural heritage in the face of Emirati dredging and fishing. Additionally, UAE businesses began providing services on the air and sea routes to the island, bypassing the Yemeni government and undermining its authority (Tamma, 2017).

At the end of April 2018, the UAE began deploying military forces, including both personnel and armour, to Socotra (McKernan, 2018). They quickly seized control of the port and airport in Hadibu. Yemen’s internationally-recognised Prime Minster, Ahmed Bin Daghr, protested the UAE’s actions after being allegedly prevented from leaving the island, stating that “What the UAE is doing in Socotra is an act of aggression” (Al Jazeera, 2018); at the same time Yemeni President Abdrabbuh Mansur Hadi lodged a formal complaint with the UN Security Council over the “unjustified military actions” (The New Arab, 2018). Saudi attempts at mediation led to a partial withdrawal of Emirati troops in May, but the UAE has maintained and slowly expanded its presence since then.

Today, the UAE still acts as a de facto authority on the island and has been strengthening ties between it and the UAE mainland amidst local protestations. In February 2019, Socotrans were offered a range of job opportunities based in the Emirates (Igrouane, 2019), and military buildups have reportedly continued apace with redeployments of South Asian mercenary units and Yemeni separatist militias to the island (Middle East Monitor, 2019).

3. How do states exert control over maritime chokepoints?

These two cases illustrate three different approaches by which China and the UAE have sought to establish control in Bab el-Mandeb: commercial, military, and diplomatic.

Securing commercial control

Companies (including shipowners, port services providers, brokers, and others) play a large role in the control of global maritime trade. This provides an opportunity for state involvement through nationally-owned corporations. While there is a clear profit motive for controlling infrastructure on busy shipping lanes, state involvement is also rewarded by the ability to manipulate variables such as port schedules, berthing priority, and customs checks to their advantage.

State participation in commercial interests can be clearly observed in the case of DCT, where both of the companies involved in the dispute are state-controlled. DP World is owned via a subsidiary company by Dubai World, a government-owned holding company (Dubai World, 2019), and Hong Kong-based CMPH is owned and controlled by the Chinese government through China Merchants Group. CMPH considers itself a “natural executor of the Belt and Road Initiative” (China Merchants Port: ‘Investment not limited to Ports’, 2019). This places the company near the core of China’s economic strategy and gives it ample political and financial backing.

Prior to 2018, the UAE had established control over commerce in the strait through DP World’s port services contracts at and part ownership of DCT. However, financial backing from the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) enabled CMPH’s extensive investment in Doraleh Multipurpose Port and paved the way for their takeover at DCT.

This shifted the balance of commercial power decisively in China’s favour. The Emirati responses effected through DP World reveal a continued focus on retaining control over commerce in Bab el-Mandeb. Their legal challenges to Djibouti’s seizure of the port have focused not only on financial compensation, but also on upholding the original concession agreement. While not likely to change the de facto situation, this indicates that the UAE still considers their presence in Doraleh to be of vital interest. The second response from DP World was to ramp up investment elsewhere in Bab el-Mandeb and sign agreements with nearby competitors, notably Eritrea’s Assab and Somaliland’s Berbera (Dahir, 2017). This attempt to wrest back control over regional commerce has initiated a treadmill effect in the region, with different actors (notably Saudi Arabia and Ethiopia in addition to China and the UAE) pouring money and resources into infrastructure projects in an effort to keep pace with each other (International Crisis Group, 2019).

Approaching maritime chokepoints in this way - through securing indirect, commercial control over the activity in their ports - is a strategy that is enabled by deterritorialization and globalization. Both DP World and CMPH derive their strength in the situation from large scales. They are able to effectively leverage the power of globally mobile capital and trade to build and defend their local interests. DP World also relied on the globalization of legal systems to defend their commercial interest. The case was brought before standardised, international courts such as the London Court of International Arbitration in an attempt to scale the dispute up to a level where they felt they were in a stronger position.

Establishing military presence

The second strategy that we can observe is the establishment of military presence around bottlenecks, most evident in the UAE’s actions on Socotra. There, armed forces were used to establish control over a strategically important territory, and with it the maritime routes that it sits on. The continued use of force and violations of Yemeni sovereignty by the UAE have led to classification of these actions as a de facto colonization or annexation. The takeover is also easiest to justify from a military point of view. Socotra’s port is in a commanding position, but is rarely visited by passing vessels; control over it therefore provides little commercial gain. However, the island has significant strategic value for military purposes thanks to the airport’s long runway, from which control and surveillance can be extended over the busy shipping lanes. This is reminiscent of the historical examples outlined above, in which colonial powers sought to control ports with little value beyond their ability to project power into the sea.

Military access also plays a role in the DCT case study. Five different countries (Japan, Italy, France, China, and the USA) maintain military bases in Djibouti for combating piracy and protecting shipping in the region; while these do not seek to control infrastructural assets in the same way as the UAE’s takeover of Socotra, they still allow for the projection of force into the surrounding areas. These bases rely on Doraleh for supply. America’s AFRICOM, for example, receives 90% of its materiel through Doraleh and views access to DCT as “a U.S. strategic imperative” (USAFRICOM, 2019, p.35). In 2017, China opened its first overseas military base adjacent to DCT, where the People’s Liberation Army Navy now reportedly has a dedicated berth (Melvin, 2019).

In contrast to this accommodation, one of the early issues in the DP World/Djibouti relationship was Djibouti’s refusal to allow the Emiratis to use DCT as a staging point for military operations across the strait in Yemen, constricting their ability to project hard power in Bab el-Mandeb.

Taken together, these observations show that countries still place a great deal of importance on maintaining a military presence in maritime chokepoints. This is a traditional geopolitical, territorializing approach to the issue, and the one famously espoused by Mahan. However, it is still impacted and in some cases constrained by the process of globalization. This can be seen in two ways in our case studies. First, in the setbacks that the UAE encountered in Socotra; in addition to territorial contestations from Yemen, Abu Dhabi’s military action was temporarily inhibited by pressure resulting from appeals to global, deterritorialized organisations such as the UN.

Second, we can see globalization’s influence in the constellation of military bases surrounding Doraleh. Of these, the Japanese, Italian, Chinese, and American military deployments were all originally justified as supporting multilateral anti-piracy efforts such as the EU’s Operation Atalanta or NATO’s Operation Ocean Shield (Melvin, 2019) - an initiative that matches Harvey’s depiction of decentralised, global institutions. Only France, Djibouti’s former colonial power, did not use such a justification to begin their military presence in the country. As such, we observe that global processes of deterritorialization serve to constrain the territorializing behaviour of states in the maritime arena by, to paraphrase Harvey, allowing peripheral powers to insert themselves into the geopolitical competitive game.

Fostering diplomatic relations

The commercial and military strategies that we have observed have been bolstered by the use of diplomacy to inuence local actors in both of these case studies. In Djibouti, the foundations for the Chinese takeover of DCT can be found in the extensive relationship developed between the governments of Djibouti and China. Scaling up infrastructure requires significant investment, and for Djibouti this has come primarily from China through the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Djibouti’s debt to China is equivalent to 75% of the country’s GDP (Hurley, Morris, & Portelance, 2018), leaving the government reliant on Chinese goodwill in order to balance their budget.

This ’debt diplomacy’ is a common feature of Chinese foreign policy through the BRI, and serves (among other things) to use financial leverage to influence local actors to act in ways that benefit China. The Chinese government has used this diplomatic strategy extensively along maritime trade routes to extend control over bottlenecks and defend Chinese trade interests (“China’s “maritime road” looks more defensive than imperialist”, 2019), so DCT is by no means a unique example of this.

Similarly, the UAE had extensive diplomatic relationships in place in Yemen before taking military action on Socotra. These ties were built with several actors in the fractured political landscape of Yemen. The UAE built goodwill with the internationally recognised Yemeni government through its participation in the international coalition fighting alongside President Hadi against Houthi rebels in the north of Yemen. At the same time, they fostered close ties with separatist groups in South Yemen - particularly the Southern Transitional Council (Igrouane, 2019). These engagements served to weaken opposition to the UAE’s actions on Socotra in the same way that Chinese debt did in Djibouti; they made the Yemeni government largely reliant on the UAE and diminished their ability to act against Abu Dhabi’s interests.

The provision of aid in the wake of cyclones Chapala and Megh was not overtly military in character, but it began to normalise Emirati involvement on the island and built positive relations with the inhabitants. It also served as a way for the Emirati government to deflect any international criticism of their actions on Socotra, as demonstrated by reportage in their state-owned news outlets (Al-Karimi, 2017).

These diplomatic strategies also operate in recognition of the territorialized nature of their localities. The need to build relations with actors who hold or claim sovereignty over the territories in question is a feature that constrains territorializing and deterritorializing processes alike, so such diplomatic approaches are necessary to support either military or commercial goals.

4. How do these strategies relate to local scales?

While it is easy to view maritime bottlenecks such as Bab el-Mandeb from a global perspective, they exist first and foremost within their geographic localities. As Eriksen and Tsing emphasise, it is important for us to view global processes from below as well as from above. In this case, examining the local conditions in Doraleh and Socotra will provide context on both the consequences and determinants of the influencing strategies outlined above.

In Djibouti there is little evidence of change at the scale of the port’s operations. However, both the country and the region have been an integral part of the competition over DCT. Being the most stable country in the region and home to suitable geography for deepwater ports, it is a natural site for commerce in the region. This explains why soft-power approaches such as commercial domination and base-building have been favoured in Djibouti.

However, the influence is not only upwards - the commercial and diplomatic strategies taken by China have left Djibouti suffering from a serious lack of flexibility. First, because it has overdeveloped Djibouti’s logistics industry so heavily that the country is now reliant on it - Doraleh itself is emblematic of this issue as both the largest employer and largest revenue generator in the country (Lohade, 2018). Second, the debt diplomacy outlined above has left the Djiboutian government reliant on China, constraining their ability to act independently and seriously reducing their flexibility.

Within the Horn of Africa, Djibouti has a significant impact on other countries’ economies – as the only modern deepwater port in the Horn of Africa, Doraleh is the primary link between the sea and the region’s hinterlands. This economic clout is particularly evident in neighbouring Ethiopia. The growing scale and complexity of their economy has left landlocked Ethiopia reliant on foreign imports, 95% of which enter the country through Djibouti (Ethiopia Observer, 2018). Because of this inflexibility, Ethiopia has been a willing participant in efforts to diversify the region’s ports and reduce the commercial control enjoyed by DCT; Addis Ababa has invested alongside DP World in developing the port of Berbera and normalised relations with Eritrea to access the port of Assab. Ethiopia has thus influenced other actors towards commercial strategies in the region and is prepared to benefit from their outcomes as well.

In Yemen, the relationship between the local scale and the actions of global powers is clear. The instability arising from Yemen’s protracted civil war makes commercial approaches unfeasible, but it also provides both opportunity and cover for military action. Socotra itself has been destabilised by the UAE’s actions, with residents divided along pro- and anti-UAE lines. Protests and counter-protests have become common occurrences on what used to be a largely forgotten part of Yemen (Chappelle, 2019). Yemen’s internationally-recognised government has also suffered from Abu Dhabi’s military and diplomatic strategy - not only have they been shown to be weak in the face of occupation, but they must also now contest with emboldened separatist groups backed diplomatically and financially by the UAE. The Emirati participation in the Saudi-led coalition has also been impacted by these events. Along with Abu Dhabi’s actions in Aden, they have strained cooperation between the partners in the region (Daily Sabah, 2019), and risk further complicating an already intractable conflict.

Comparing these two cases reveals the importance that local conditions play in determining how states approach strategic chokepoints. The very different strategies that the UAE has pursued in this region – commercial contestation in Djibouti and military action in Socotra - are made possible because of the stability (and therefore commercial attractiveness) of Djibouti and the contrasting instability (and weakness) of Yemen.

At the same time, we can draw two distinctions between the local impacts of the three strategies described above: stabilizing/destabilizing over short timescales, and increasing/decreasing flexibility in the immediate region. China’s and the UAE’s commercial competition over DCT has been destabilizing for the region – operators have been removed, inland trade routes have changed, and new ports are being built. However, the competition which is responsible for this instability has also provided flexibility to the region as commerce is diversified. Abu Dhabi’s military action on Socotra has been similarly destabilising, both for Yemen’s territorial integrity and for the coalition of allies fighting in the ongoing civil war. However, it has not provided any local increases in flexibility for the region. Finally, the diplomatic strategies used by both China and the UAE have both had stabilising influences over the short term by providing much-needed support to the Djiboutian and Yemeni governments. However, they have also come at the cost of regional flexibility as the decision-making process of both local governments has been constrained by their reliance on foreign goodwill.

5. Scope for further study

To fully understand the range of state responses to maritime chokepoints, further research is needed. Continued monitoring of developments in Bab el-Mandeb and other global bottlenecks is crucial to building an understanding of how differing local conditions impact states’ involvement. Developing a connected set of databases relating to diplomatic, commercial, and military information at shipping chokepoints would enable truly comparative studies across a range of academic disciplines. These three core datasets could be represented in a single GIS-based framework as outlined below.

First, diplomatic approaches to influence over bottlenecks should be recorded. Such a database would focus on those who control territory around chokepoints and how foreign powers interact with them. It would need to detail political discourse including statements, agreements, and summits, but it should also track actualised support. This should include data on national debt levels and creditors, provision of foreign aid, and concrete support such as arms transfers. The bulk of this high-scale data is already possible to obtain, but localising it to one platform alongside the other datasets envisaged for this app would provide valuable context to any analysis in this field.

Second, to track commercial influence, a similar approach would be taken to infrastructure. This database would be built to include ports, terminals, shore-side storage, and canals near chokepoints. This scope could be expanded in future (for example to key secondary infrastructure such as railways or pipelines leading out of ports). Two different types of data would be required for each entity: the physical details (e.g. location, maximum draft, storage capacity, annual throughput) and the business details (e.g. ownership history, operators). Much of this data is already available in various states of completeness to corporations via costly subscription services.

Third, military activity around chokepoints would need to be monitored. This should be done in consideration of both capability (size, location, complexity, and ownership of military installations and fleets) and operations (patrols, participation in task forces, clashes, etc.). Naturally not all of this information is freely available, so public sources would need to be augmented by open source intelligence efforts where possible.

A final area for further research is how states utilise their control over these chokepoints once it has been established. Shipping data, drawing from existing AIS (Automatic Identification System)-tracking applications could be utilised here. This would follow the global shipping fleet and provide key data points for each vessel – locational tracking, cargo type, deadweight, owner, flag, etc. This information is already readily available in public and proprietary software, so should prove simple to acquire. Analysis of this data will enable researchers to answer questions about the material advantages gained by control over chokepoints: do vessels of certain flags receive beneficial treatment, do controlled facilities become ports of convenience, etc.

6. Conclusion: how do states interact with maritime chokepoints in the 21st century?

Through our studies of Doraleh Container Terminal and the UAE’s actions in Socotra, we can observe three methods by which states attempt to exert control over maritime chokepoints: commercial, military, and diplomatic.

These three methods represent different responses to the globalized environment of the 21st century. Commercial approaches are based in this global system and leverage deterritorialized systems of capital, trade, and law to establish and maintain power in maritime bottlenecks. In contrast, military strategies for control of these spaces are inherently territorializing and mirror the geopolitical approach of Mahan and the early colonial empires. They are, however, constrained by the deterritorialized systems of the modern world and require justification in the eyes of multilateral or global institutions. Both of these approaches are supported by the third - diplomacy.

The local environments in which they play out impact both the selection and outcome of these strategies, and are in turn altered by them. The differences between Djibouti and Socotra have led to competition between the UAE and China for commercial control in the former, and unilateral military action by the UAE in the latter. The impacts of the strategies on small scales also vary - both military and commercial competition have short-term destabilising effects on the region, but the competition promoted by China’s commercial strategy has increased the region’s flexibility. Concurrently, the use of diplomatic means to encourage dependence on both the UAE and China have reduced local flexibility in both cases while providing short-term stability to the region’s governments.

This is a rich topic which deserves further study encompassing different actors, timeframes, and regions. The integrated databases suggested in this paper would provide a valuable tool for investigating this topic further and developing a greater understanding of how states exert control over global processes at sea.

References

Al Jazeera. (2018, May). UAE forces ’occupy’ sea and airports on Yemen’s Socotra. Al Jazeera. Retrieved from https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2018/05/uae-forces-occupy-sea-airports-yemen-socotra-180504181423573

Al-Karimi, K. (2017, Apr). UAE offers a helping hand to the island of Socotra. The National. Retrieved from https://www.thenational.ae/opinion/uae-oers-a-helping-hand-to-the-island-of -socotra-1.6185

Ballard, G. A. (1928). Rulers of the Indian Ocean. New York;Boston;: Houghton Mifflin Company.

Blouet, B. W. (2004). Geopolitics and globalization in the twentieth century. London: Reaktion Books.

Broeze, F. (2017). The globalisation of the oceans: Containerisation from the 1950s to the present. Liverpool University Press.

Chappelle, A. (2019, Nov). Yemen’s Socotra residents divided in conflict. Al Jazeera. Retrieved from https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2019/11/yemens-socotra-residents-divided-conict-191104160023224.html

Chatham House. (2017). Chokepoints and Vulnerabilities in Global Food Trade. Chatham House. Retrieved from https://reader.chathamhouse.org/chokepoints-vulnerabilities-global-food-trade#

China merchants port: ‘investment not limited to ports’. (2019, Mar). Belt and Road News. Retrieved from https://www.beltandroad.news/2019/03/21/china-merchants-port-investment-not-limited-to-ports/

China’s “maritime road” looks more defensive than imperialist. (2019, Sep). The Economist. Retrieved from https://www.economist.com/graphic-detail/2019/09/28/chinas-maritime-road-looks-more-defensive-than-imperialist

Dahir, A. L. (2017, Apr). The UAE is expanding its influence in the Horn of Africa by funding ports and military bases. Quartz Africa. Retrieved from https://qz.com/africa/955585/in-somalia-and-eritrea-the-united-arab-emirates-is-expanding-its-inuence-by-building-ports-and-funding-military-bases/

Dahir, A. L. (2019, Feb). A legal tussle over a strategic African port sets up a challenge for China’s Belt and Road plan. Quartz Africa. Retrieved from https://qz.com/africa/1560998/djibouti-dp-world-port-case-challenges-chinas-belt-and-road/

Daily Sabah. (2019, Mar). Saudi, UAE tension over Socotra island reportedly continues. Daily Sabah. Retrieved from https://www.dailysabah.com/mideast/2019/03/27/saudi-uae-tension-over-socotra-island-reportedly-continues

Deleuze, G., & Guattari, F. (1977). Anti-oedipus: capitalism and schizophrenia. New York: Viking Press.

Deleuze, G., & Guattari, F. (1988). A thousand plateaus: Capitalism and schizophrenia. London: Athlone Press.

Die, B. W., & Winius, G. D. (1977). Foundations of the Portuguese empire, 1415-1580 (N - New ed., Vol. 1.). Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Dodds, K. (2009). Geopolitics. Los Angeles: SAGE.

Dubai world. (2019). Retrieved from http://www.dubaiworld.ae/

EIA. (2017). World Oil Transit Chokepoints. Retrieved from https://www.eia.gov/beta/international/regions-topics.php?RegionTopicID=WOTC

Eriksen, T. H. (2016). Overheating: An anthropology of accelerated change. Pluto Press. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1cc2mxj

Ethiopia Observer. (2018, Apr). Djibouti, Ethiopia strike port deal, Djibouti to partner in Ethiopian airlines, telecom. Ethiopia Observer. Retrieved from https://www.ethiopiaobserver.com/2018/04/29/djibouti-ethiopia-strike-port-deal-djibouti-to-partner-in-ethiopian-airlines-telecom/

Graham, G. S. (1965). The politics of naval supremacy: studies in British maritime ascendancy (Vol. 1964.). Cambridge Cambridgeshire UK: Cambridge University Press.

Gray, S. (2018). Investigating the coal question. In Steam power and sea power: Coal, the royal navy, and the british empire, c. 1870-1914 (pp. 13–38). London: Palgrave Macmillan UK. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-57642-2_2 doi: 10.1057/978-1-137-57642-2_2

Grotius, H., & Armitage, D. (2004). The free sea. Indianapolis, IN: Liberty Fund, Incorporated.

Harvey, D. (1995). Globalization in question. Rethinking Marxism, 8 (4), 1-17.

Holmes, J. R., & Yoshihara, T. (2008). Chinese naval strategy in the 21st century: the turn to Mahan (Vol. 40.). Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

Hurley, J., Morris, S., & Portelance, G. (2018). Examining the Debt Implications of the Belt and Road Initiative from a Policy Perspective. Center for Global Development. Retrieved from https://www.cgdev.org/sites/default/les/examining-debt-implications-belt-and-road-initiative-policy-perspective.pdf

Igrouane, Y. (2019, Apr). Is the UAE Gearing Up to Annex Yemen’s Socotra Island? Inside Arabia. Retrieved from https://insidearabia.com/uae-gearing-up-annex-yemens-socotra-island/

International Crisis Group. (2018). The United Arab Emirates in the Horn of Africa. Retrieved from https://d2071andvip0wj.cloudfront.net/b065-the-united-arab-emirates-in-the-horn-of -africa.pdf

International Crisis Group. (2019). Intra-Gulf Competition in Africa’s Horn: Lessening the Impact. Retrieved from https://www.crisisgroup.org/middle-east-north-africa/gulf -and-arabian-peninsula/206-intra-gulf -competition-africas-horn-lessening-impact

Koburger, C. W. (1992). Naval strategy east of Suez: the role of Djibouti. New York: Praeger.

Kosai, S., & Unesaki, H. (2016). Conceptualizing maritime security for energy transportation security. Journal of Transportation Security, 9 (3), 175-190.

Lohade, N. (2018, Feb). Djibouti seizes strategic DP World container terminal. Wall Street Journal. Retrieved from https://www.wsj.com/articles/east-african-country-seizes-strategic-dp-world-container-terminal-1519408714

Mahan, .-., A. T. (Alfred Thayer). ([1911] 1991). Naval strategy. Washington, DC: U.S. Marine Corps.

McKernan, B. (2018, May). Socotra is finally dragged into Yemen’s civil war, ripping apart the island’s way of life. The Independent. Retrieved from https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/middle-east/socotra-yemen-civil-war-uae-miltary-base-island-life-emirates-a8342621.html

Melvin, N. (2019). The foreign military presence in the Horn of Africa region. Retrieved from https://www.sipri.org/publications/2019/sipri-background-papers/foreign-military-presence-horn-africa-region

Middle East Monitor. (2019, Sep). Arrival of more UAE mercenaries on Yemen’s Socotra island. Middle East Monitor. Retrieved from https://www.middleeastmonitor.com/20190906-arrival-of -more-uae-mercenaries-on-yemens-socotra-island/

Moran, D. (2002). The international law of the sea in a globalized world. In S. J. Tangredi (Ed.), Globalization and maritime power (p. 551-561). Washington, D.C.: National Defense University Press. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-57642-2_2 doi: 10.1057/978-1-137-57642-2_2

Paris, C. (2019, Feb). China tightens grip on east African port. Wall Street Journal. Retrieved from https://www.wsj.com/articles/china-tightens-grip-on-east-african-port-11550746800

Tamma, P. (2017, May). Has the UAE colonised Yemen’s Socotra island paradise? The New Arab. Retrieved from https://www.alaraby.co.uk/english/indepth/2017/5/17/has-the-uae-colonised-yemens-socotra-island-paradise

The New Arab. (2018, May). Yemen complains to UN about UAE military occupation of Socotra Island. The New Arab. Retrieved from https://www.alaraby.co.uk/english/news/2018/5/10/yemen-complains-to-un-about-uae-occupation-of -socotra

Tsing, A. L. (2005). Friction: an ethnography of global connection. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press.

USAFRICOM. (2019, Feb). Statement of General Thomas D. Waldhauser, United States Marine Corps Commander United States Africa Command before the Senate Committee on Armed Services. Retrieved from https://www.armed-services.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/Waldhauser_02-07-19.pdf

Wilson, T. (2018, Sep). Djibouti nationalises shares in key red sea port. Financial Times. Retrieved from https://www.ft.com/content/7c349544-b4ef -11e8-bbc3-ccd7de085e

Wirtz, J. J. (2002). Will globalization sink the navy? In S. J. Tangredi (Ed.), Globalization and maritime power (p. 551-561). Washington, D.C.: National Defense University Press. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-57642-2_2 doi: 10.1057/978-1-137-57642-2_2

WTO. (2019, Sep). WTO data. World Trade Organisation. Retrieved from https://data.wto.org/